by Valdis Krebs

We are all happy to live in the modern world of massive connectivity. We can connect to, receive products from, or do business with anyone in the world — distance no longer seems to matter. Shoes from China, beef from Argentina, software from India, wool from Scotland, guitars from Spain, and cartoons from America — they are all to be had in any city in the world. The products and services we buy often travel long distances, and are made/delivered by people not only physically far, but also socially distant — often we do not even speak the same language, nor have the ability to create a common context with the people creating the products we buy.

Giant markets, on-line and off, such as Walmart and Amazon, shrink the world and bring us products and services, we would not be exposed to in our daily wanderings from home to work to recreation. We increasingly put our trust into, and give our money to, large organizations that play the role of “Queen Between” in the modern marketplace. With big economic players spanning the globe, our consumer horizons are almost unlimited — strawberries in the middle of winter, step-by-step tracking of our new Apple computer from the factory in China to our front door, the best wines from France delivered to our home in Ohio in time for Thanksgiving. The world indeed is small — just choose, pay, and anticipate. Globalization is great.

Yet, this model of trusting unknown, distant producers and their vendors may be in jeopardy. The seller with an octopus reach into all corners of the world, may be reaching too far.

I was witness to an interesting conversation amongst mothers in Latvia — a poor country still trying the shake the shackles of 50 years of Soviet economic and political oppression. We were all enjoying a typical dinner of sauerkraut, potatoes, smoked sausage, and beer. The sausage was exceptionally tasty with several people commenting on its naturally smoked goodness. Eventually the question came up, “Where did you get these?” The answer was not one of the big European supermarket chains that now criss-cross the country, nor was it the huge central marketplace in the heart of Riga. “I got them from an old lady that my mom introduced me to” was the answer. “My mom took me there one day and said this is where you get certain items” “Going with my mom was the introduction I needed to the lady behind the counter — this told her I was OK, and vice versa.” One of the guys at the dining table also lauded the sauerkraut. Same story — one stall at the local outdoor market has the best just-fermented cabbage which is the main ingredient in the Latvian recipe of sauerkraut (every country/region seems to make it different).

Another Mom spoke up, “Yeah, I have noticed that my friends and I shop less and less at the big supermarket chains and we are getting back to visiting a few select local vendors who have foods of better quality and taste. I like it that I we can trace where the food came from!” She continued, “You know it is weird, it is almost like in Soviet times when you had to know someone at the meat store to get a good cut of meat — otherwise you had to settle for the slop they sold to everyone.” “I just saw at the supermarket they were selling beef from Argentina for the same price as European beef — they ship it all that way, at huge cost, and then they sell it for a low price! What the heck is wrong with it? What did they do to it? I won’t buy that!” She was on a roll, “We all started shopping the major supermarket chains that rolled in after the Soviet Union fell. We were happy to have clean, modern stores with a variety of goods available. But now I find myself going back more and more to local vendors who seem to have fresher, unadultered, and tastier food… for a very good price.”

The other mothers shook their head in agreement. Soon they all came up with examples of how they avoid the large supermarket networks for various food items. All of them had a short chain to a producer of a certain staple. As they were talking and exchanging information I started to visualize the various networks in my head — there was the dairy network (fresh non-homogenized milk delivered to your house from the dairy farmer), the potato network, the egg network(all Latvian hens are “free range”), the smoked meats network, the fish network. It appeared the most staples had a network that connected various city dwellers to farmers and fisherman that would come to town on a regular schedule. These farm-to-city networks were self-organizing and grew via mouth-to-mouth recommendations. Many of these families utilized the supermarkets for brand-name items or imported fruits and vegetables (i.e. avocados, oranges, etc). If the item was available locally they usually had a network that was connected to a trusted local source at a reasonable price — direct access without middlemen, mark-ups, and delays!

Local farmer’s (open air) markets thrive in Latvia — even during the cold winters. Families create bonds with certain sellers and pass these connections on to friends and family. No one is cheated or goes without when the bonds of trust between buyer and seller are embedded in a dense network where everyone knows most everyone else. Vendors know, if they cheat, or sell bad food, word will get around and people will avoid them. I have seen this in the various markets — two adjacent stalls selling highly similar items, one has a line and the other is ignored. Trust, once broken is hard to mend, especially when it is so public.

Not only is back-to-the-source “local food” popular in small European countries. We see the movement in the United States also. Many farmers markets are sprouting up in all medium to large cities. People don’t want apples from China that have been picked green and sprayed with who knows what. They want to look the farmer in the eye and ask about spraying, chemicals and harvesting methods. Many of the better restaurants in all cities pride themselves on locally sourced food items on the menu. Some menus list the source of today’s products on the back of the menu. A farmer can have no better advertising than to be selected by the area’s best chefs.

What we are witnessing here are some simple network dynamics. Distance is a key dynamic in networks. The further the distance, the less visibility and less knowledge about what is going on at that distance. Greater distance generally results in less trust.

Human networks consist of connections between people. Not everyone is connected to everyone else. We can only manage so many connections (they take time and energy to maintain) so we have to choose our connections carefully. In choosing our connections we are often driven by homophily — an academic term for: birds of a feather flock together. Not everyone is the same, and since we tend to connect with those most like us, our immediate connections are very similar. But the further away we go, in terms of connections, the less likely those people in the network will be like us. The friends of our friends will be less like us than our direct friends — and friends of friends of friends(3 steps away), will be even less like us.

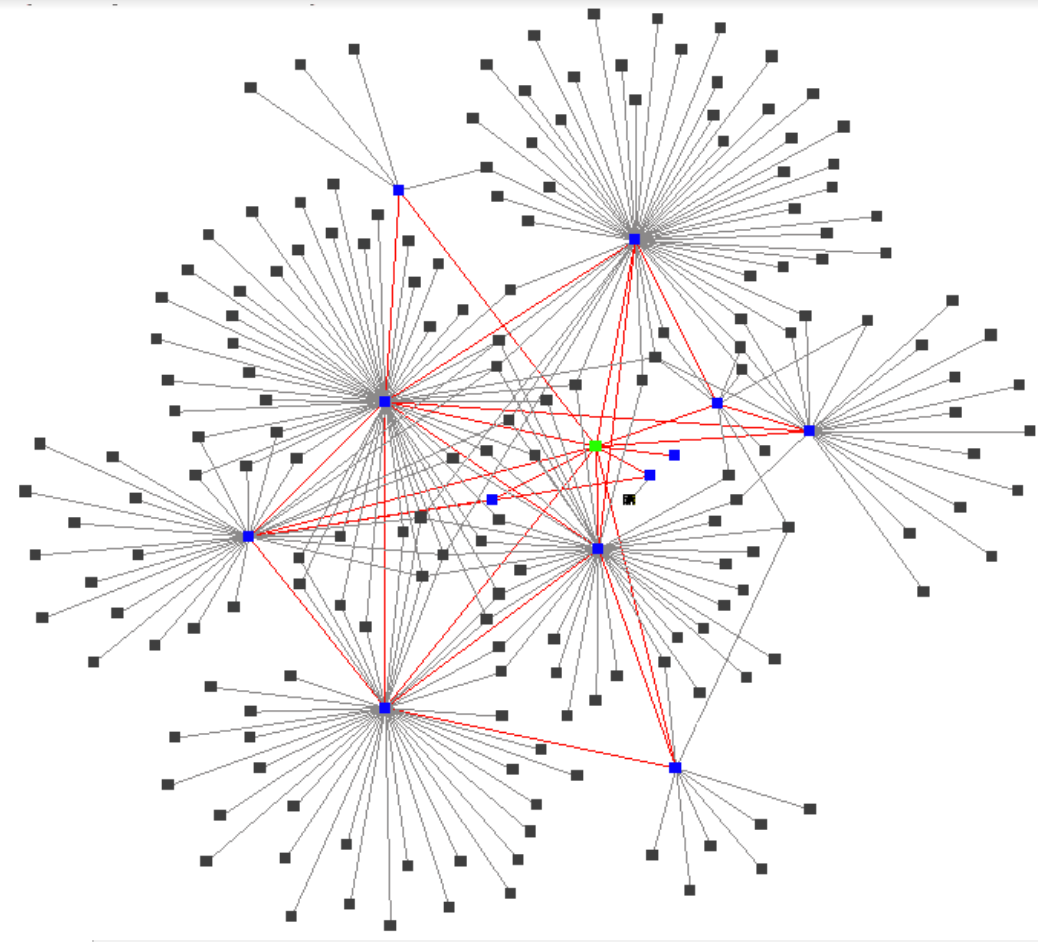

Researchers have found that as we go further and further away in our network of links, we see less and understand less. There is a horizon in our networks beyond which we are blind to see/understand what is happening. The research shows this horizon appears to be between 2 and 3 steps out from us. We know our friends and colleagues well, they are our direct contacts and are 1 step out from us. Their friends and colleagues (2 steps out from us), are visible and knowable to us, but things already start to get fuzzy — we are not aware of all of our 2-step contacts. At three steps (friends of friends of friends) things start to get real foggy and fuzzy and we know just a little about about what is happening at this level of our network horizon. Beyond three steps we are blind and powerless about what is happening in our network. All we know about people 4 or more steps away from us is the public information about them, which is available to everyone.

Above is a the network horizon for a person who is represented by the green node in the middle. The person’s direct (1-step) contacts are in blue, and the indirect contacts (2-steps) are in grey.

It is hard to develop trust with people more than 2 steps away, unless we have the relationship ensconced in legal documents. Most executives, vendors, suppliers, and resellers involved in the food business are 4 or more steps away from the end-buyer. Unless they are selling a popular brand, we may not be very open to trusting them. Farmer’s markets and open air markets reduce the network distance between seller and buyer from 4 or more, down to 1 or 2 — you are either buying from the farmer or one of his/her trusted representatives. The woman with the great smoked sausage, mentioned above, bought it directly from the meat smoker. He explained his smoking process to her. She trusted it, and passed that trust on to her clients — those preparing home and restaurant meals. Just last week I watched a Sunday morning show in Riga with a famous local chef. It was all about his suppliers — he visited each one, bragging about how good their produce was. You could sense the warmth and affection between chef and his suppliers. Even if something went wrong in their exchange, you could sense that they would work it out and become smarter in the process. I trust going to restaurant where the chef knows his sources and his sources are eager to provide top quality ingredients. Of course you pay more for the results of a well-functioning network, but the food and experience are worth it. You do get what you pay for!

Where else do you see small trusted vendors thriving in economic networks? Many places — from consulting services, to event planning, to art, photography, and music, and anywhere else where quality matters and people don’t mind paying for what they get. In the end, everyone gets what they pay for, and quality ends up being the prudent alternative — just ask anyone who has bought cheap clothes, tools, food, and other supplies. The error of your ways is usually quickly apparent.

Brands seem to be another form of trust. People stick with brands that have proven to work out well in the past. LL Bean, Apple, Toyota, are brands that consistently receive great buyer reviews. Certain vendors sell many brands but always focus on making sure the customers are happy — Amazon, Nordstrom and Costco are vendors that can sell just about anything because people trust that they will be satisfied with the purchase — the seller will make it right. Even though these vendors are beyond your network horizon, and products they sell are even further out still, the public reputation and individual experience of customers results in healthy markets where everyone wins. If you sell brands and support your customers you can thrive beyond the the 3rd step in a purchaser’s network.

Who sells the best stuff for a fair price quickly percolates through a human network, as does bad news about untrustworthy vendors. Markets are social — they are conversations, knowledge exchanges, arguments, and learning experiences. Some vendors realize this and act accordingly, whether they are Apple, or they sell apples, they know that the network knows.

For those looking for quality products and experiences they will join networks that know. From the wine network, to the organic food network, to the vegan network, to the musician network, all have local knowledge that can help any member of the network. People will find those who know and those who know “who knows.” In active networks of fast information flow and knowledge exchange the good vendors will thrive, whether they provide one item or a menu full. Local networks will reveal who to stand in line for, and who to route around. The internet, along with on-line services such as “Angie’s List” distribute this information even faster. But hearing a positive or negative story from someone within your network horizon has a lot more clout than hearing from unknown person on the internet. We tend to believe those who know us, and share our contexts. As our horizon shrink, and become more focused, they become more powerful and useful for filtering what we need to know. Enjoy your small world of delectable knowledge!

Valdis Krebs

Orgnet,LLC

Twitter: orgnet